| Description |

: |

Married January 16, 1873 in Jefferson county, Iowa.

-----------

Fairfield Daily Ledger

Monday October 31, 1927

Pg. 1 Col. 4

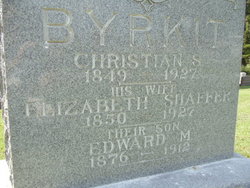

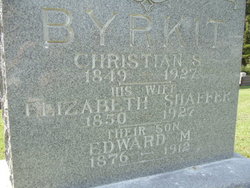

C. S. BYRKIT PASSED AWAY

At His Home In Des Moines; Remains To Be Brought Here Wednesday

C. S. Brykit passed away this morning at 10 oclock at his home in Des Moines after having been in very poor health for a long time. The remains will be brought to this city Wednesday noon at 12:01 over the Burlington and will be taken directly to Evergreen cemetery where short services will be conducted by Dr. U. S. Smith. The body will be intered (sic) beside his...

Read More

|

Married January 16, 1873 in Jefferson county, Iowa.

-----------

Fairfield Daily Ledger

Monday October 31, 1927

Pg. 1 Col. 4

C. S. BYRKIT PASSED AWAY

At His Home In Des Moines; Remains To Be Brought Here Wednesday

C. S. Brykit passed away this morning at 10 oclock at his home in Des Moines after having been in very poor health for a long time. The remains will be brought to this city Wednesday noon at 12:01 over the Burlington and will be taken directly to Evergreen cemetery where short services will be conducted by Dr. U. S. Smith. The body will be intered (sic) beside his wife, who was buried here last June following her death from an auto accident.

Mr. Brykit is survived by the following children: Mrs. A. E. Pray and R. D. Brykit of Des Moines and Harry Brykit of Peoria, Ill.

Mr. Brykit's wife was a sister of Mrs. W. E. Johnson, 301 East Burlington street.

-----------

"Annals of Iowa",

Vol. XIV, July 1923,

Pgs. 95-100

A DERAILMENT ON THE RAILWAY INVISIBLE

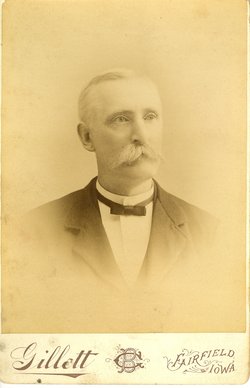

BY CHRISTIAN S. BYRKIT

The monotonous intonation of swift revolving wheels carrying the C. B. & Q. express in its onrush up through "Pumphrey's Pasture' of other days, was momentarily overcome by a long shrill whistle from the great mogul engine. As I peered out upon the city's electrically lighted and paved streets, reminiscence carried me back some sixty years to the days when this now triving (sic) city of more than 6,000 people, with its factories and excellent institutions of learning, was but a village of perhaps 1,200 people, and I, a school boy of fourteen years, practically knew them all.

But strenuous events were even then swiftly succeeding each other, forerunners in history. In 1861 the Civil War was on in earnest, and Jefferson County with a population of but 15,000, of whom 720 were called to the colors, responded by an enrollment of 966, or practically a full regiment. Strong men, physically fit! Good people have always lived there, but in Civil War times, when inspired public meetings commenced promptly at "early candle lighting," and loyalty was the paramount issue, the vestal fires never burned low.

Not to have known James F. Wilson, Christian Slagle, George Acheson, Ward Lampson, Captain Wells, the elder Jordons, William Junkin, and others, patriots all, and a few whose names linger in memory only as a dream, was not to have known Fairfield in its crucial analysis.

Father came to Iowa in 1816. Our forebears were French Huguenots, "used to war's alarms." Years of determined armed resistance against those regarded as unduly solicitous for the welfare of their souls, finally culminated in the great tragedy of St. Bartholomew's Day, and thereafter the Huguenots sought refuge in the Netherlands, only to be confronted by more drastic restriction of their religious and personal liberties, which, during thirty years of warfare following, they stubbornly resisted; then in large numbers they removed to the "land of the free," where under the caption of Quakers, they became prominent factors in the settlement of many northern states, including Iowa.

These Quaker immigrants landed largely in Pennsylvania, because of having acquired the Dutch dialect, but they early found their way in large numbers up the Shenandoah and Piedmont valleys into North Carolina, establishing settlements at Ashville, Salem, Mecklenburg, New Berne and other places. But their bitter antipathy to human slavery caused many to again take up the trail, spreading over Kentucky, Tennessee, and north beyond the Ohio River, where still deeply imbued with their peculiar religious ideas, their tribal name soon became a synonym of honesty, integrity, and ideal citizenship. Yet, strange as it may appear, every such community in the North automatically became a station harboring colored refugees traveling upon the hypothetical "underground railway" leading to Canada and freedom.

Perhaps 1859 was the crucial year for American slavery. A weak-minded chief justice of the Federal Court, now almost forgotten, had recently handed down a decision that Negro slaves, male or female, possessed "no rights which the white man was bound to respect." An atrocious attempt to bring Kansas into the Union by force, as a slave state, was frustrated largely through the efforts of John Brown, an eccentric character of Quaker stock, whose hostility to human slavery was well known, who withstood and drove back the Kansas invaders. Later Brown attempted an insurrection at Harper's Ferry, Virginia, was captured and with his immediate adherents, a meager support, executed. Unnecessary haste and unwarranted display of military authority marked conspicuously the incident. No doubt these events ultimately became formidable factors in the national election of 1860, which precipitated the great civil conflict between the states, ending in the complete overthrow of slavery in this country.

Fairfield is delightfully situated upon almost level ground. At the time under review, the town abruptly terminated on the north at a rapid descent of the ground towards a small stream of water known as Crow Creek. The main traveled road passed over this branch on a small wooden bridge, and made it rise again to the level of a country outlined with beautiful cultivated farms. On the east side of this road, contouring to the descent and reaching almost to the creek, was located the old time graveyard. The intervening space between the creek and graveyard, as well as both sides of the creek, was heavily wooded.

After crossing the old bridge and regaining the level, farms began to appear, the first being one in which father was interested. In the wood which I have described, several hundred yards east of the bridge, secreted by the timber, in close proximity with the graveyard and creek, was an old dilapidated, deserted slaughter house, once used in the preparation of meat for the town market. This shack bore the unenviable reputation of being haunted. Father, stoical, like his class of people, usually gave little credit to spook stories. Such beliefs were taboo in our home. But publicly he conceded, although reluctantly, the possible truthfulness of the prevailing old slaughter house stories.

Occasionally, as the war clouds thickened and neighbors grew suspicious of each other, my mother would hand me an old grain bag half filled and, if in the presence of others, direct me to salt the stock at the farm. Without comment I received the bundle as a matter of little consequence, and whistling to keep up courage, went to the old bridge, and if no one was in sight, plunged into the wood, and at the "haunted" cabin never failed to find a Negro refugee. Sometimes they had been cruelly beaten, but invariably were optomistic (sic). I was always surprised how one of these people could eat a whole loaf of homemade bread, a large chunk of cooked meat and six or eight boiled potatoes, the entire contents of the bag, and get away with it, but I never knew a failure.

These were refugees from Missouri slavery, I think. But my parents did most of the thinking. Direct from the Quaker settlement at Salem, Henry County, these refugees were spirited by sympathizers and piloted to coverage among the Quakers at Pleasant Plain, or Richland, thence on northeast through Iowa to Canada.

Upon leaving the slaughter house, an hour or two was spent conspicuously at the farm house near by, then the old horse was saddled, a little old muzzle-loading shotgun hung by a strap, breech down, upon the saddle pommel. Huguenots seem always to have divided their faith about equally between God and the blunderbuss. Thus equipped I cautiously picked my way through the gathering darkness, down to the old cabin where "Jim Crow," a common appellation, for to me these people all looked alike, was taken on behind the saddle. Cautiously and noiselessly we slipped up through the woods, striking the main traveled thoroughfare about the Bayard farm. Here our speed might be increased slightly while crossing the prairie. Sometimes the refugee would become hilarious as he imagined freedom was the next stop, but a vigorous back elbow punch, accompanied by a sharp command to "shut up" painfully reminded him of the old overseer, and silence oppressive would follow. Finally more woodland slipped past, until we came to a clearing a few hundred feet wide stretching across west, and to another road. It was instruction, if in turning into this clearing the moon showed, "hug" the north wall of trees, lying low on the neck of the horse. One unpleasant feature which menaced the rider was the persistency with which the man behind would cling to his person, thereby greatly impeding his movements, and evoking the constant admonition, "Don't hold on so, Jim."

The moon came and went as the clouds floated over us, one night, tempting me to indiscreetly accelerate our gait. However, we clung close to the wall of woods. Jim Crow had just loosened his body hold as we sharply rounded the corner into the road, when we came abruptly upon two horsemen engaged in earnest conversation. The reining of our horse was so sudden and violent as to set him back upon his hind quarters. Jim, taken at a disadvantage, disappeared backward, derailed, so to speak, upon the "right of way." The breech of the gun struck the hard road bed, became unlimbered from the saddle horn, fell over towards the strangers, was discharged by the concussion, and sent up through the darkness a stream of fire which seemed to reach the clouds. And noise! Pandemonium holds no record over that uproar.

Our horse, frightened beyond control, bounded forward and a race was on. Persuasion and assurance finally brought him again into submission, a mile or more over the road.

Crossing back to the east road, I returned to the farm, restabled the horse, and minus my cap, walked into town, called at the butcher shop—markets we call them now—secured some steak for breakfast, as I had been instructed the evening before, and betook myself home by way of the back gate. I had failed ingloriously. What would father think? He would say nothing; he was a fatalist.

It was growing daylight, but I did not observe a man in the alley, who strode over and demanded authoritatively where I had been. Hatless and the wrapped meat proved a sufficient alibi. How did I get out of that house? Easy. "Went out at the front door." "See a man there?" "No." Something like "H---l," was his exclamation as he faded away. It seemed apparent, the watchman at the front had slept on the job. Following a quiet breakfast, I gathered my books and set out for school. I was seeking no interview.

A little knot of six or eight men gathered near a livery barn were discussing something out of the usual. Approaching the group I noticed two strangers, one of whom undoubtedly I had mot in the alley that morning. As I approached the spokesman was talking in a tragic manner. "Just then," he said, "a dozen or more men came suddenly upon us, firing their guns, by which one of our 'hosses' was badly crippled. Before we could recover from our surprise, they escaped down the road." "It's a disgrace," sympathetically exclaimed a neighbor who was under surveillance on account of his disloyal tendency and utterances. The little old shotgun was in evidence. It was broken down at the grip, the breech piece hanging by the carrying strap. Who could identify it and thus establish ownership ? Every family in those days owned a gun, for wild game was abundant. At once it seemed the consensus of opinion that I, being acquainted with every gun in the neighborhood, could solve the problem. In a spirit of bravado I accepted the challenge, sparring for time by a critical examination of the weapon. This turn of affairs did not seem to even startle my ever complacent father who had meanwhile joined the group. After mature deliberation I ventured the opinion that the gun was the property of a neighbor, well known for his covert, unpatriotic utterances. At this sudden turn of affairs several guffawed and snickered, others sneered and turned away. The meeting adjourned.

Toward evening a venerable old Quaker farmer from the northern part of the county drove slowly up to our house, called me out and after looking carefully around to ascertain if we were alone, he produced my lost head gear, with the laconic inquiry: "Son, is this thy cap?" "Yes, uncle Josiah." "Well, thee should be more careful where thee hangs it up," and with this parting admonition he drove away.

This was my last emergency call. As an engineer on the underground railroad, I had lost my run through lack of caution. What came of the colored man I never knew. Father, if he was advised, never spoke of it, but I always felt that he was proud of my effort; and duty well done, with a Quaker, needs no encomium. I am of opinion that in the confusion, the colored man escaped unnoticed, into the woods, not more than ten feet away, and was later rescued and passed along.

Those were heroic days, but they were not lived in vain.

|